This post is an update on the Pyjion project to plug the .NET 5 CLR JIT compiler into Python 3.9.

.NET 5 was released on November 10, 2020. It is the cross-platform and open-source replacement of the .NET Core project and the .NET project that ran exclusively on Windows since the late 90’s.

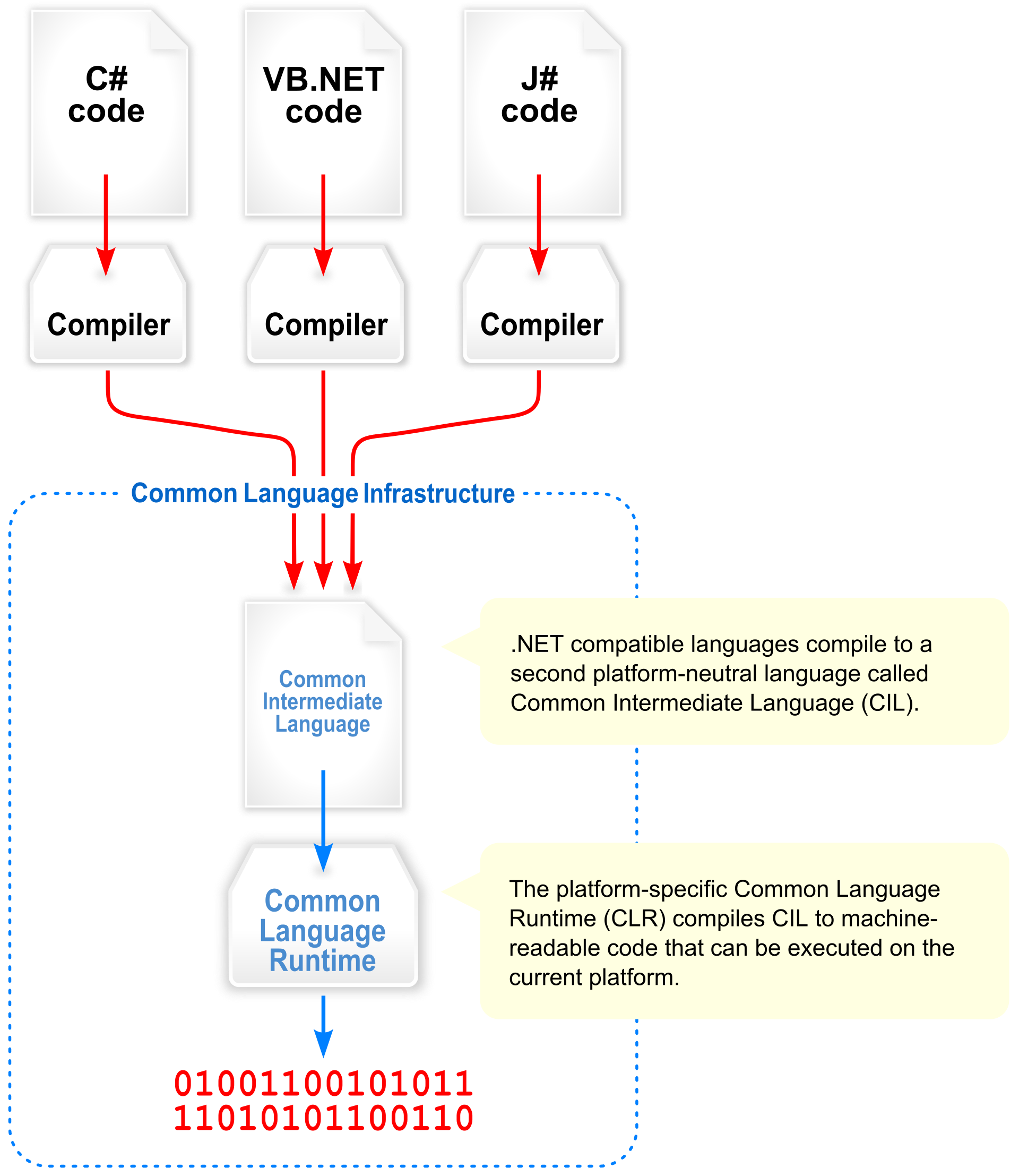

.NET is formed of many components:

- 3 builtin languages, C#, F# and VB.NET, each with its own compiler

- A standard library

- A common intermediate language to abstract the high level languages from the core runtime. This is a standard known as ECMA 335 CIL.

- A common language runtime (CLR) that compiles CIL into native machine code so that it can be executed and packages executables into .exe formats.

.NET 5 CLR comes bundled with a performant JIT compiler (codenamed RyuJIT) that will compile .NETs CIL into native machine instructions on Intel x86, x86-64, and ARM CPU architectures.

You can write code in a number of languages, like C++, C#, F# and compile those into CIL and then into native machine code (as a binary executable) on macOS, Linux, and Windows. Pretty neat.

But this is a blog about Python. So what does this have to do with Python?

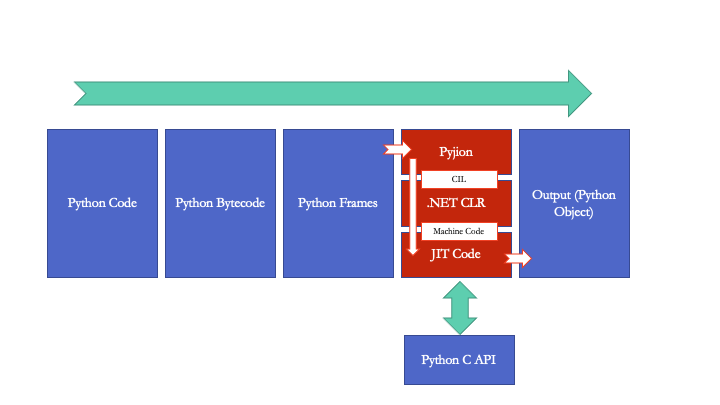

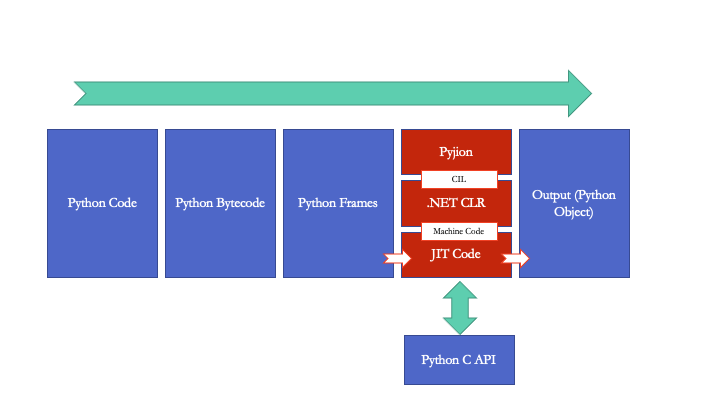

Pyjion is a project to replace the core execution loop of CPython by transpiling CPython bytecode to ECMA CIL and then using the .NET 5 CLR to compile that into machine code. It then executes the machine-code compiled JIT frames at runtime instead of using the native execution loop of CPython.

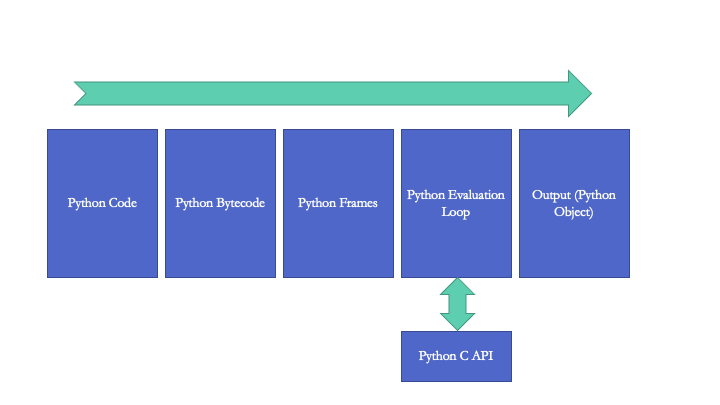

Very-quick overview of Python’s compiler¶

When CPython compiles Python code, it compiles it into an intermediate format, similar to .NET, called Python bytecode. This bytecode is cached on disk so that when you import a module that hasn’t changed, it doesn’t compile it every time. You can see the bytecode by disassembling any Python function:

>>> import dis

>>> def half(x):

... return x/2

...

>>> dis.dis(half)

2 0 LOAD_FAST 0 (x)

2 LOAD_CONST 1 (2)

4 BINARY_TRUE_DIVIDE

6 RETURN_VALUE

To execute anything on a CPU, you have to provide the OS with machine-code instructions. This can be accomplished by compiling them up-front using a compiled like the C or C++ compilers. They compile code into executable formats as either shared libraries or standalone executables. See my post on Python/assembly for a bit more info on this topic.

CPython converts the bytecode into machine code instructions like looping over them in a precompiled function, called the evaluation loop. This is essentially a big for loop with a switch statement. The compiled version of CPython that you’re running already has the instructions required. This is why CPython’s evaluation loop is an “AOT”, or “Ahead of Time” compiled library:

Note: There is a lot more to CPython’s compiler. I’ve written a whole book on the CPython compiler and the internals of CPython if you want to learn more.

There are a few issues with this approach. The biggest is speed. A series of inline machine-code instructions is very performant. CPython has to make judgements at runtime for which code branch to follow every time your function is run. This leads to CPython being 100x slower in “tight-loop” problems where its executing the same thing again and again. The machine-code is compiled ahead of time and it has to loop around to get to the right instructions. Checkout my PyCon talk for a more in-depth explanation:

The most common way around this performance barrier is to compile Python extensions from C. This produces a custom binary with inline machine-code instructions for the task at hand. This is how most machine-learning and data science libraries like numpy, pandas, SKL are put together. This approach is still AOT compiling the code. It also requires a lot of knowledge of C. This approach has worked really well for the data science community, where algorithms can be performant and leverage low-level platforms like GPUs or specialised AI chipsets.

There are a few issues with the AOT extension module approach. One is that it still uses the evaluation loop. C extension modules are a set of functions. Once you call the C-compiled function, its in the performant code, but your Python code that’s calling it still lives inside Python’s loop. If you want to leverage a compiled library and your Python code is doing some heavy number crunching, you end up having to use an API of functions, like numpy, instead of a more fluent Python API:

>>> import numpy as np

>>> a = np.ones([9, 5, 7, 4])

>>> c = np.ones([9, 5, 4, 3])

>>> np.dot(a, c).shape

(9, 5, 7, 9, 5, 3)

>>> np.matmul(a, c).shape

(9, 5, 7, 3)

What Pyjion does to solve this issue¶

A few releases of Python ago (CPython specifically, the most commonly used version of Python) in 3.7 a new API was added to be able to swap out “frame execution” with a replacement implementation. This is otherwise known as PEP 523. PEP 523 also added the capability to store additional attributes in code objects (compiled Python code.

Pyjion does not compile Python code. It compiles Python frames (code objects, like blocks, functions, methods, classes) into machine-code at runtime using a performant JIT:

CPython compiles the Python code, so whatever language features and behaviours there are in CPython 3.9, like the walrus operator, the dictionary union operator, will all work exactly the same with this extension enabled. This also means that this extension uses the same standard library as Python 3.9.

Pyjion is a “pip installable” package for standard CPython that JIT compiles all Python code at runtime using the .NET 5 JIT compiler. You can use off-the-shelf CPython 3.9 on macOS, Linux or Windows. After installing this package you just import the module and enable the JIT.

Once a frame has been compiled, the binary code is cached in memory and reused every time the function is called:

Using Pyjion¶

To get started, you need to have .NET 5 installed, with Python 3.9 and the Pyjion package (I also recommend using a virtual environment).

After importing pyjion, enable it by calling pyjion.enable() which sets a compilation threshold to 0 (the code only needs to be run once to be compiled by the JIT):

>>> import pyjion

>>> pyjion.enable()

Any Python code you define or import after enabling pyjion will be JIT compiled. You don’t need to execute functions in any special API, its completely transparent:

>>> def half(x):

... return x/2

>>> half(2)

1.0

Pyjion will have compiled the half function into machine code on-the-fly and stored a cached version of that compiled function inside the function object.

You can see some basic stats by running pyjion.info(f), where f is the function object:

>>> pyjion.info(half)

{'failed': False, 'compiled': True, 'run_count': 1}

You can see the machine code for the compiled function by disassembling it in the Python REPL.

Pyjion has essentially compiled your small Python function into a small, standalone application.

Install distorm3 first to disassemble x86-64 assembly and run pyjion.dis.dis_native(f):

>>> import pyjion.dis

>>> pyjion.dis.dis_native(half)

00000000: PUSH RBP

00000001: MOV RBP, RSP

00000004: PUSH R14

00000006: PUSH RBX

00000007: MOV RBX, RSI

0000000a: MOV R14, [RDI+0x40]

0000000e: CALL 0x1b34

00000013: CMP DWORD [RAX+0x30], 0x0

00000017: JZ 0x31

00000019: CMP QWORD [RAX+0x40], 0x0

0000001e: JZ 0x31

00000020: MOV RDI, RAX

00000023: MOV RSI, RBX

00000026: XOR EDX, EDX

00000028: POP RBX

00000029: POP R14

...

The complex logic of converting a portable instruction set into low-level machine instructions is done by .NET’s CLR JIT compiler.

All Python code executed after the JIT is enabled will be compiled into native machine code at runtime and cached on disk. For example, to enable the JIT on a simple app.py for a Flask web app:

import pyjion

pyjion.enable()

from flask import Flask

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route('/')

def hello_world():

return 'Hello, World!'

app.run()

That’s it.

Will this be compatible with my existing Python code? What about C Extensions?¶

The short answer is- if your existing Python code runs on CPython 3.9 – yes it will be compatible. To make sure, Pyjion has been tested against the full CPython “test suite” on all platforms. In fact, it was the first JIT ever to pass the test suite.

Thats because this isn’t a Python runtime, it uses the existing Python compiler to compile your code into Python bytecode (low level instructions).

Pyjion uses the same dynamic module loader as CPython, so if you import a Python extension from your virtual environment, it will work just the same in Pyjion.

Project History¶

Pyjion isn’t new. Brett Cannon and Dino Viehland started the Pyjion project 4 years ago. This was the first JIT to pass the full CPython test suite. There were some limitations to the original proof-of-concept:

- Written against an old version of .NET Core

- Required custom patches of .NET and compiling from source

- Required custom patches of CPython and compiling from source

- Only worked on Windows

- It was written for Python 3.6 before PEP 523 was agreed and merged

Has much changed since Python 3.6? To the average user, not really. But under the hood, the implementation of a few things has completely changed:

- Function calls

- Iterators

- Exception Handling

- Dictionary, list and set comprehensions

- Generators and coroutines

Actually, a lot has changed in the last few releases of CPython. The new fork to get Pyjion working with the latest version of everything was a big undertaking…

The goal with the latest patch was to get the project up to the condition of:

- Using the release binaries of .NET 5 and CPython 3.9

- Making it work across all platforms

- Implement the PEP523 interface

- Implement all the new features of Python 3.9

- Making the package “pip installable” from PyPi

- Improving the test coverage

- Adding a disassembler (both machine-code and CIL) to aid development

Is this faster?¶

The short answer a little, but not by much (yet).

JIT compiling something doesn’t make it faster. Actually, the overhead of compiling functions the first time they are called often makes it slower.

JIT compilers are faster because of optimizations at runtime. A good JIT compiler will make assertions about the function that its compiling and how it behaves to optimize out code paths, shortcut calls and inline instructions. This can make drastic differences.

However, Pyjion doesn’t do that. Yet. The goal with this patch was to build a solid foundation on which optimizations could be written and tested.

There will now come seperate patches to try writing optimization phases.

The .NET JIT does have some optimizations for CIL->machine-code, but it has absolutely no knowledge of Python, types or structure. This needs to be written in Pyjion.

I think these optimizations will be game-changing in terms of performance gains for Python.

Here are some basic ideas I’ve been thinking about and it would be great to test:

- An optimizer for string parsing and dictionary lookups that would make template compiling in Jinja2 or Django faster

- An optimizer for unrolling small comprehensions or loops that would make general code faster

- An optimizer for integers and floats to use machine-code instructions for binary arithmetic instead of the Python C-API

- An optimizer for Unicode string encoding

Does this help me use my .NET libraries from Python?¶

Short answer is no.

Long answer is that CIL has two types of instructions, primitive and object-model. The CIL specification has an entire standard for object declaration, types, equivalence etc. Pyjion converts Python bytecode into primitive CIL instructions. Python bytecode itself is mostly primitive. There are some exceptions, like specialised bytecodes for declaring lists, dictionaries and tuples. But most of the work to convert classes, functions and fields into primitive types happens further up the chain. Therefore it would be a huge undertaking to implement object-model interfaces for Python.

If you want to do this, I recommend checking out Python.NET.

Comparison with other projects¶

Checkout Brett’s comprehensive answer to this question.

Future potential¶

There are some potential benefits to this project:

- A general purpose JIT could build optimizations in areas that are unloved, especially web applications

- Having a pip-installable JIT that is compatible with all CPython code is a huge benefit to making everyday applications faster

- It doesn’t require a bespoke build toolchain to use it

- Packaging compiling frames into a portable executable format like .EXE PE files

Awesome, how do I install it?¶

Checkout github.com/tonybaloney/pyjion. For now, compile from source. I am also publishing from precompiled wheels onto PyPi.

It is very-much alpha. Don’t deploy to production*

* unless its Friday.

Credits¶

- Thank you to Andy Ayers at Microsoft for helping me figure out the Windows pointer offset issue and the helper function API.

- Thank you to Steve Dower at Microsoft for helping me figure out the dynamic library loader.

- Thank you Dino and Brett for doing the heavy lifting to get the original POC together.