Toward the end of 2024, there were a bunch of releases and announcements for new AI models. In particular, there was a lot of discussion about models which can do “complex reasoning” and “chain of thought” to solve complex problems. The noisier opinions around AI cover a spectrum from “we have almost reached AGI (Artificial General Intelligence)” to “this thing is a glorified auto-correct”.

I’m still somewhere in the middle. I find the idea of anyone using them for complex reasoning quite baffling as I still see large numbers of users struggling to get them to answer simple questions consistently. In short, I continue to be surprised and disappointed with LLMs in equal balance.

I’ll work on a demo, try it 10 times, show it to colleagues. Then, when doing the exact same thing on stage, it behaves totally differently. It is frustrating to say the least. For now, I’m putting that down to my own lack of skill and the newness of these tools. Especially after watching colleagues masterfully get the same model to produce quality responses to complex inputs.

One technique that I’ve been curious to dig deeper into is this addition to a system prompt: If you don't know the answer, say <the magic word>.

Now, an LLM doesn’t know anything. It gives you the most probable answer. But you can instruct an LLM to admit when it doesn’t have a good answer instead of hallucinating?

We’re going to explore that in this post.

Why has Harry Kane won the Ballon D’or so many times?¶

Take this example question:

Why has Harry Kane won the Ballon D’or so many times?

Apologies to any non-European soccer fans for the obscurity of the question. Harry Kane is one of the top goal scorers European football. The “Ballon D’or” is a (very political) trophy given annually to the best soccer player in the world, judged by a panel of journalists.

The AI’s response starts with:

Harry Kane has won the Ballon d’Or multiple times due to his exceptional goal-scoring abilities and consistent performance at the highest level of football. In 2024, he shared the Ballon d’Or Gerd Muller Trophy with Kylian Mbappe for scoring the most goals in Europe [1]

This test was on a GPT-4 based RAG application that uses Internet searches as the retrieval mechanism to ground it’s answers. It references a BBC Sport article talking about Harry Kane winning the Gerd Muller Trophy (awarded in the same ceremony.) The opening sentence “Harry Kane has won the Ballon d’Or multiple times” is flagrantly wrong. Harry Kane has never won this award. Harry Kane’s lack of trophies relative to his performance is something of a sore point. Soccer is the most watched sport in the world and the Ballon D’or the most famous trophy. If this were a Pub Trivia question it would be included in the warm-up round.

If I ask the question slightly differently in the same session:

Has Harry Kane ever won the Ballon D’or?

It responds:

Harry Kane has not won the Ballon D’or.

So, did he win the Ballon D’or or not? What’s happening here? A colleague asked the same question in a different geography and it used a different source to respond that Harry Kane has never won the Ballon D’or.

I asked the same question to a deployment of vanilla GPT’s to see if the BBC sport reference and RAG process was confusing the LLM and got these responses:

| Model | Response |

|---|---|

| gpt-4o (2024-11-20) | As of my knowledge cutoff in October 2023, Harry Kane has not won the Ballon d’Or even once, let alone multiple times. |

| gpt-4 (turbo-2024-04-09) | Harry Kane has not won the Ballon d’Or. |

| gpt-35-turbo | Harry Kane has never won the Ballon D’or. |

As alluded to earlier, the behaviour and unpredictability of these LLMS is still a mystery to me (and I’m not alone). But I think we can see some of the root cause in the default system prompt for GPT models:

“You are a helpful assistant”.

I am a helpful assistant!¶

“You are a helpful assistant” is the default system prompt in ChatGPT and many other GPT/LLMs. Azure OpenAI defaults to “You are an AI assistant that helps people find information.”. A helpful assistant would answer the question I gave it and not respond “what are you talking about you fool, Harry Kane has never won the Ballon D’or”. If we changed the prompt slightly to say “You are a sports pundit“, or “You are a helpful sports journalist“, would it improve the quality of the answer?

In Zheng, Pei, Logeswaran, et al’s study When “A Helpful Assistant” Is Not Really Helpful: Personas in System

Prompts Do Not Improve Performances of Large Language Models, they tried experimenting with different generic personas like you are a colleague/buddy/friend. They also tried experimenting with domain-specific personas, like you are a biologist/ecologist/baker.

Through their analysis they found that it made very little difference.

The only times I’ve seen the persona make a noticeable difference to the output is when it includes a language-specific persona like “you are a sulky teen”, or “you are Jar-Jar-Binks”. Never had I seen it give more factual or accurate responses because of the persona I told it to inhibit.

So can we solve this problem a different way? Going back to my observation about colleagues masterfully getting the LLM to work well, they’d been adding this suffix to the end of system prompts:

If you don’t know the answer, say “I don’t know”.

Does it work?

The Big Fib¶

On long car journeys we listen to a podcast for kids called “The Big Fib”. On the show, they have a topic and two guests. One is an expert and the other is a confident liar. It is then the task of a child to interrogate both guests and determine which one is the real expert.

The liar uses a combination of educated guesses, some quick research and completely made-up facts to answer the questions. The kid asking the questions has done a little research but they’re really going on “vibes” to determine who is the liar.

We must’ve listened to 100 episodes of this show because we live in Australia and every car journey is a long one. I’ve worked out a little trick to catch out the liar. In the quick-fire round at the end of the show, the expert will pass on questions when they don’t know the answer. The liar will make something up. They never pass.

The liar is the helpful assistant.

The expert is the original source of information.

The kid is you. The user.

I’m drawing this analogy because in the show, the liar’s job is to respond to questions. Confidently. It has some knowledge. A combination of common-sense and research. They also make things up for comedic effect which the LLM shouldn’t be doing.

But as the user it’s really hard to distinguish between the real expert and the fake one.

In our design of system prompts, we’re giving the LLM the instructions to be knowledgeable, confident, and helpful. It is mimicking the expert.

Does the extra prompt make a difference?¶

Let’s try another prompt. Instead of the helpful assistant, we’re going to give an additional instruction for what to respond when the LLM doesn’t know the answer.

You are a helpful assistant. If you don’t know the answer, reply with a shrugging emoji.

I’ve configured GPT-4o as the model for this experiment. Asking it a nonsense question as a test:

Cat. Potato. Salad.

The reply is:

🤷♀️

Let’s try something a little harder:

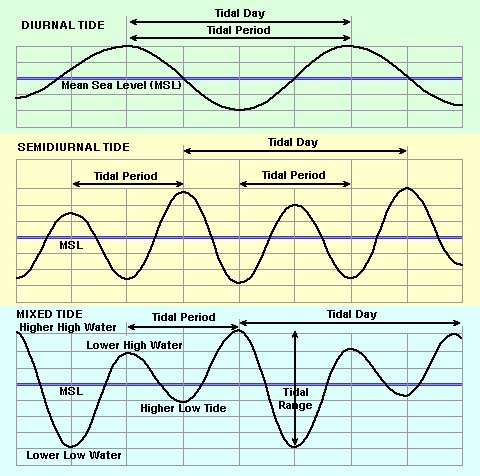

Write a 10 line Python program to calculate the tide patterns in 3 different geographies.

This is a very hard question. Tidal curves are complicated and determined by a huge range of factors.

If we were playing the Big Fib, I would expect the expert (an engineer or physical oceanographer) to say something like “It’s not that simple.” then refuse to answer the question. I would expect the fibber to make up something scientific sounding but complete gibberish.

The reply is “🤷♀️” as planned. If I reset the system prompt back to “You are a helpful assistant.” and ask the same question, it attempts to respond:

While creating a full-fledged tide pattern calculation program would typically require access to real-world data (e.g., from NOAA or other oceanographic services), we can create a simplified version that uses mock data for demonstration purposes. Here’s an example of a 10-line Python program:

With the following code:

import math

def calculate_tide(location, time):

# Simplified tide calculation (mock formula for demo)

tide = 5 * math.sin((time % 24) * math.pi / 12) + 2 # Mock tide pattern

return round(tide, 2)

locations = ["Beach A", "Harbor B", "Island C"]

times = range(0, 24, 8) # Simulate tides every 8 hours

for location in locations:

print(f"Tide patterns for {location}:")

for time in times:

print(f" Time {time}:00 - Tide: {calculate_tide(location, time)}m")

There are a few problems with this code. First, it isn’t 10 lines. Even if you remove the blank lines, it’s 11. Second, the calculate_tide function, even though it is “simulating” doesn’t use the location as a factor of the simulated tidal pattern. Third, the loop doesn’t consider the day of the year or the year itself. I could go on.

The reply is useless. This is a Python script to print the position of a sine wave. If this were an interview question for an engineering role and this was the reply, I would not hire that person.

The reply includes this footer with some explanation of the response:

- Simplified Tide Calculation: This program uses a mock sine wave to simulate tidal patterns, which generally follow sinusoidal trends.

- Locations: The program calculates tide patterns for 3 geographies: “Beach A,” “Harbor B,” and “Island C.”

- Times: Tide patterns are calculated every 8 hours (e.g., 00:00, 08:00, 16:00) for simplicity.

- Output: The result is a list of mock tide levels for each location at different times.

For real-world usage, you would need tide prediction APIs or datasets. Let me know if you’d like to explore that! 🌊

Finally, to double check that we haven’t just made an AI that just replies with a shrug, let’s ask another question I’d expect a good answer to:

Write a Python program to solve a game of Set given a collection of cards

For this question I got an explanation and a valid, useful, code snippet.

In summary, after this quick test it seems like GPT-4 models are able to reply with a coded response inplace of a poor-quality answer. This technique isn’t foolproof. LLMs can take multiple paths in a response. I’ve seen (during a live demo of course) the LLM reply to say it doesn’t know the answer to a question it previously responded to.

What about complex reasoning models?¶

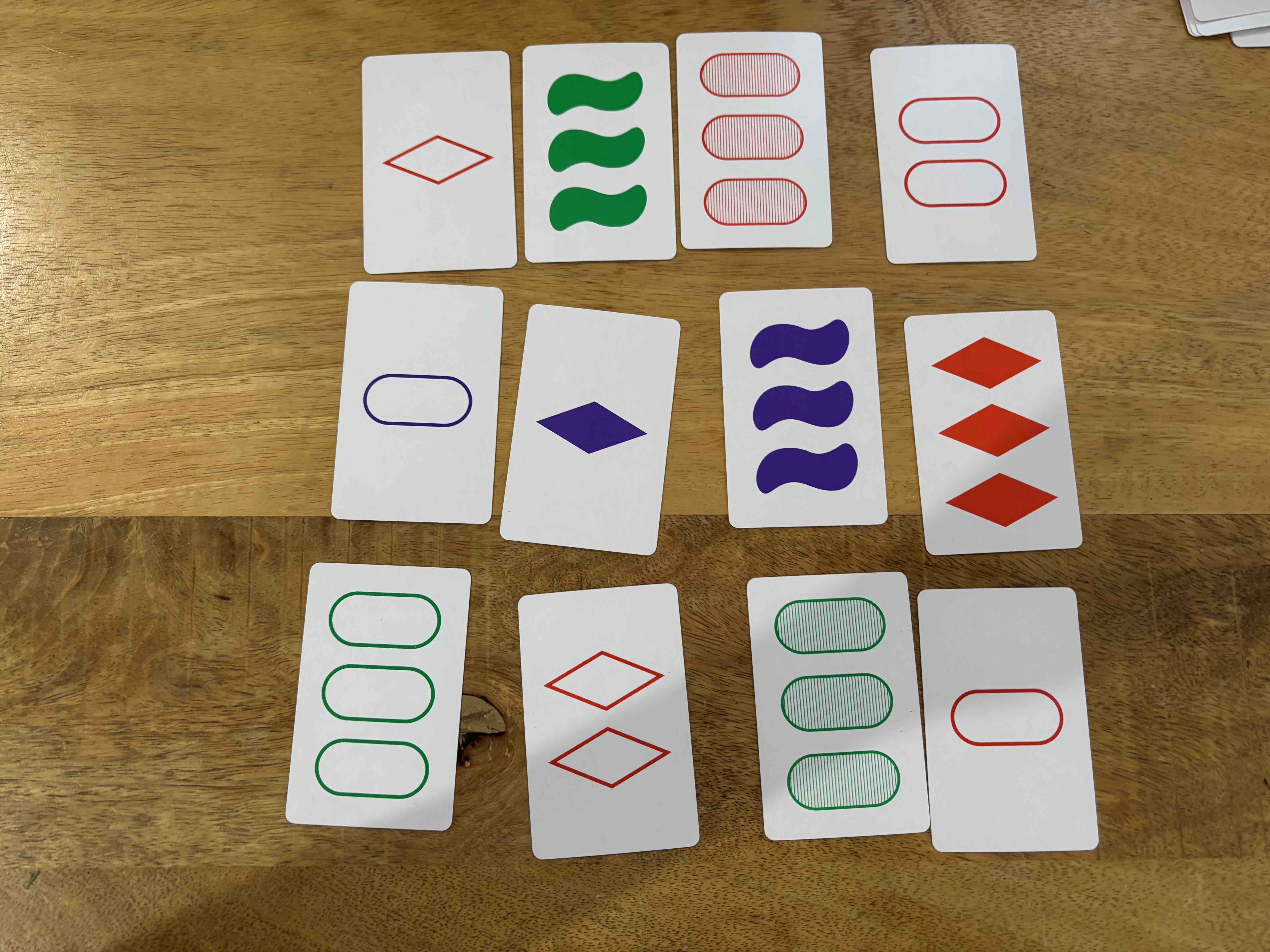

Harry Kane either did or didn’t get the Ballon D’or. What about a more complicated question? I was playing a game of Set the other day with one of my kids and we both passed on a puzzle. I quickly grabbed a photo of it to see how some of these newer AI models would respond when asked to solve it. I picked a few models that perform at-or-beyond the human grade on the MathVista visual mathematics benchmark.

If you’re not familiar with Set. It’s a fast visual perception game. Like 4-D snap. You need to spot 3 cards where the characteristics (shape, colour, number and shading) are all unique or the same.

Neither of us could see a solution in the following:

I asked GPT-4 this question and uploaded the image:

can you find a “set” in this picture?

GPT-4 eagerly explains the rules of the game then outlined it’s solution:

Sure! In the game of Set, a "set" consists of three cards where each feature (number, color, shape,

and shading) is either all the same or all different on each card.

In the image you provided, I found a set with the following three cards:

1. The card with two solid green squiggles.

2. The card with two striped purple squiggles.

3. The card with two outlined red squiggles.

These cards form a set because for each feature category (number of symbols, color, shape, and shading), the attributes are all different.

That would be a valid Set. But none of those cards exist on the photo uploaded.

GPT-4o (scores a 63.8 on MathVista) replied:

The three cards forming a Set are:

Card 1: Green ovals (3, open)

Card 2: Purple squiggles (3, solid)

Card 3: Red diamonds (3, striped)

That would be a great Set, but the third card doesn’t exist.

I asked Gemini 1.5 Flash (scores 58.4 on MathVista) the same question:

After careful examination, it appears that cards 1, 6, and 10 form a set.

* Shape: One diamond, one squiggle, and one oval.

* Color: One green, one purple, and one red.

* Number: All have one shape.

* Shading: All are open.

There are multiple errors in this response. I asked the same question again with the same image. The second time it replied “The set in the photo is the three cards in the bottom row”. There are 4 cards in the bottom row.

I asked Gemini 2.0 Flash Experimental the same question:

Yes, there is a set in the image. It's tricky!

The set is:

* The card with one red diamond.

* The card with two red diamonds.

* The card with three red diamonds.

None of the models stopped to reply that they couldn’t answer the question. Time to bring out the big-guns.

I saw in Simon Willison’s blog post in late December about a new model, QVQ-72B-Preview. This model is from Qwen and scores 71.4 on MathVista.

The response is huge, so I’ll include only a snippet from the start and the end:

So I'm trying to find a valid "set" in this collection of cards from the game of Set. I remember that in the game of Set, each card has four characteristics: number, symbol, shading, and color. For a set to be valid, each of these characteristics must be either all the same or all different across the three cards.

First, I need to understand the properties of each card. Let's look at them one by one.

Starting from the top left:

1. Red diamond, solid, one shape.

2. Green squiggle, solid, three shapes.

3. Red oval with stripes, solid, three shapes.

4. Red oval, solid, two shapes.

Moving to the middle row:

5. Purple oval, solid, one shape.

6. Purple diamond, solid, one shape.

7. Purple squiggle, solid, three shapes.

8. Red diamond, solid, three shapes.

Bottom row:

9. Green oval, solid, four shapes.

10. Red diamond, solid, two shapes.

11. Green oval with stripes, solid, three shapes.

12. Red oval, solid, one shape.

Ah, it immediately makes a fatal mistake. There are three types of shading, solid, striped and “hollow”. It labelled many of the cards incorrectly, but this is the first model I tried which actually described the cards on the table and didn’t make them up.

QVQ goes into a very long evaluation of the different combinations and determines it’s valid Set. But since the visual classification was wrong to begin with, the answer is wrong:

So, I think these are the only valid sets in these cards.

Therefore, the valid "set" in these cards is:

- Red diamond (1), Green oval (4), Purple squiggle (3)

- Red diamond (1), Red diamond (2), Red diamond (3)

- Green oval (4), Red oval (2), Purple oval (1)

But the question asks to find "a" valid set, so any one of these would suffice.

I'll go with the first one I found:

Red diamond (1), Green oval (4), Purple squiggle (3)

What about good ol-fashioned engineering?¶

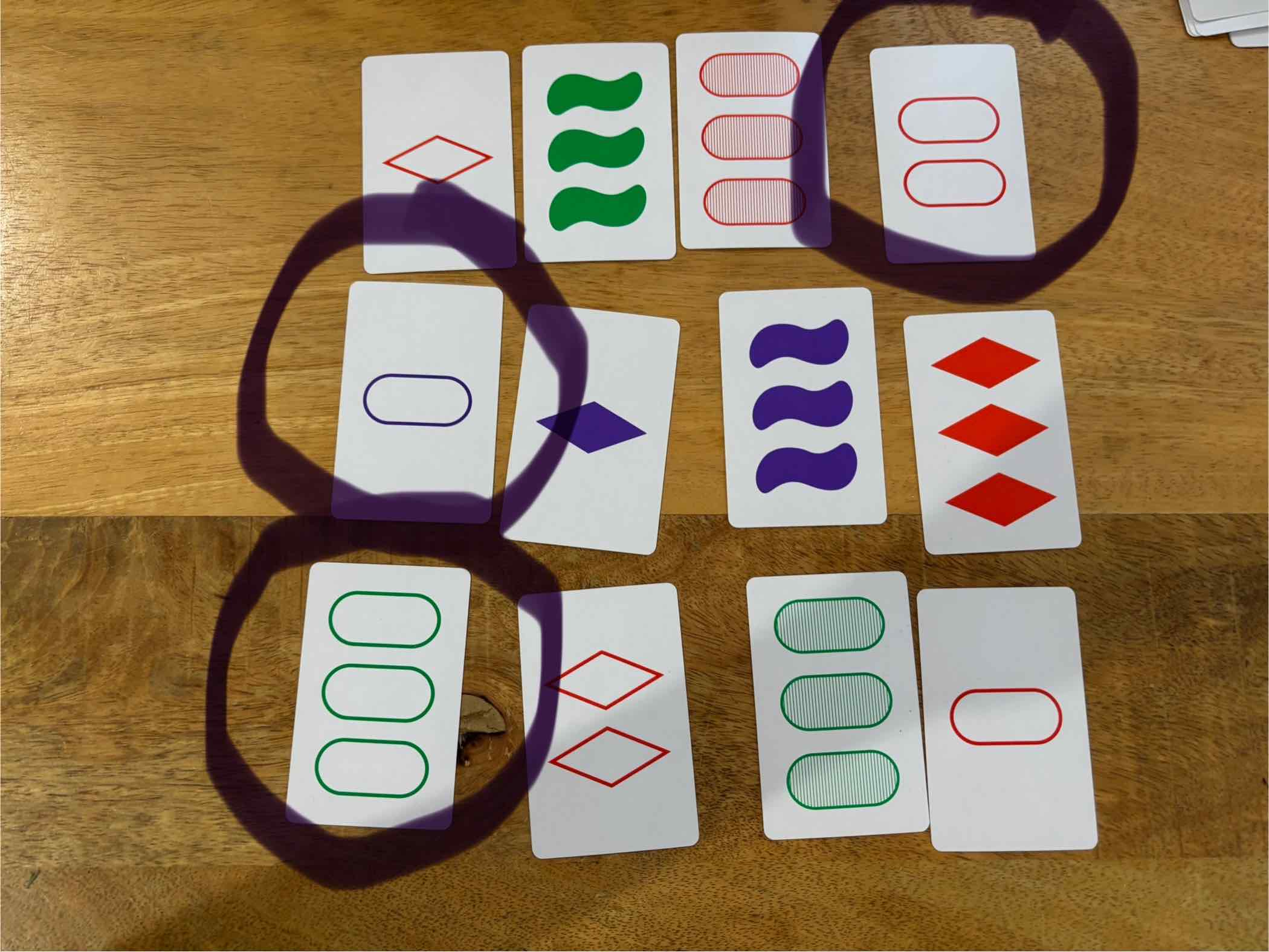

To see how complicated the question was, I disabled copilot and wrote a simple Python program to solve the Set problem:

from itertools import combinations

from collections import namedtuple

Card = namedtuple("Card", ["color", "shape", "shade", "number"])

cards = [

Card("red", "diamond", "hollow", 1),

Card("green", "squiggle", "solid", 3),

Card("red", "oval", "striped", 3),

Card("red", "oval", "hollow", 2),

Card("purple", "oval", "hollow", 1),

Card("purple", "diamond", "solid", 1),

Card("purple", "squiggle", "solid", 3),

Card("red", "diamond", "solid", 3),

Card("green", "oval", "hollow", 3),

Card("red", "diamond", "hollow", 2),

Card("green", "oval", "striped", 3),

Card("red", "oval", "hollow", 1),

]

match = None

for potential in combinations(cards, 3):

if len(set(card.color for card in potential)) in (1, 3) and \

len(set(card.shape for card in potential)) in (1, 3) and \

len(set(card.shade for card in potential)) in (1, 3) and \

len(set(card.number for card in potential)) in (1, 3):

match = potential

break

if not match:

print("No set found")

else:

print("Set found: ")

for card in match:

print(card)

Expecting it to spit out “No set found” since none of us (including the best AI models on the market) found a solution, this small bit of Python code spends a few milliseconds to print the answer that was there all along:

Oof.

I decided to go back to GPT-4o, apply the Big Fib Method and update my prompt:

Can you find the “set” in this photo? If you’re not able to answer this question reliably, tell me.

The response is the one I was seeking this whole time:

Thank you for providing the image! Unfortunately, I am not reliably able to visually analyze and identify a "Set" directly from the photo. My ability to process images is limited, and I cannot visually interpret the card attributes (color, shape, shading, and number) with absolute accuracy.

However, if you provide the attributes of the cards as a list (e.g., number, color, shading, shape for each card), I can process the data and find the "Set" programmatically. For example, you might describe the cards as tuples like (1, 'red', 'solid', 'oval'), and I can then run the algorithm to find sets.

In conclusion, the AI will be a helpul assistant unless you tell it otherwise and a very small Python program could have solved this problem in the first place.