The Python Documentary dropped this morning. In the middle of the documentary, there’s a dramatic segment about how the transition from Python 2 to 3 divided the community (spoiler alert: it didn’t in the end).

The early versions of Python 3 (3.0-3.4) were mostly focused on stability and offering pathways for users moving from 2.7. Along came 3.5 in 2015 with a new feature: async and await keywords for executing coroutines.

Ten years and nine releases later, Python 3.14 is weeks away.

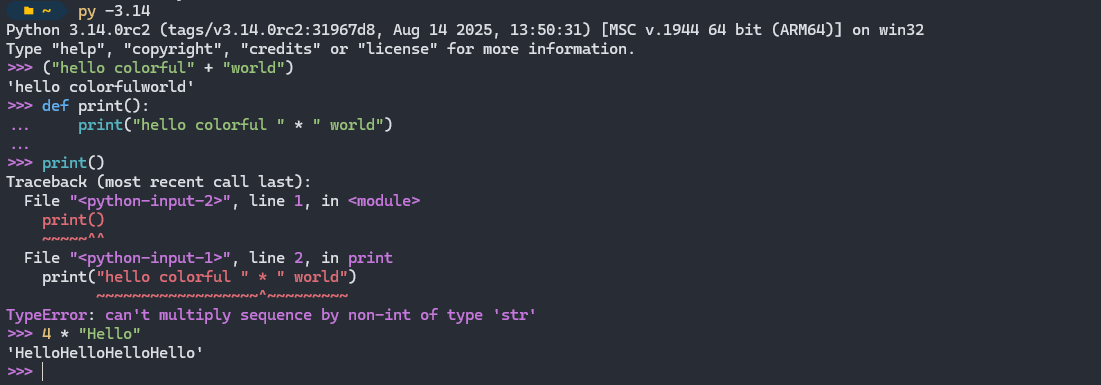

Whilst everyone will be distracted by the shiny, colorful REPL features in 3.14, there are some big announcements nestled in the release notes — both related to concurrency and parallelism

Both of these features are huge advancements in how Python can be used to execute concurrent code. But if async has been here for 10 years, why do we need them?

The killer use-case for async is web development. Coroutines lend well to out-of-process network calls, like HTTP requests and database queries. Why block the entire Python interpreter waiting for a SQL query to run on another server?

Yet, among the three most popular Python web frameworks, async support is still not universal. FastAPI is async from the ground-up, Django has some support, but is “still working on async support” in key areas like the ORM (database). Then Flask is and probably always will be synchronous (Quart is an async alternative with similar APIs). The most popular ORM for Python, SQLAlchemy, only added asyncio support in 2023 (changelog).

I posed the question “Why isn’t async more popular” to a couple of other developers to get their thoughts.

Christopher Trudeau, co-host of the Real Python Podcast, shared his perspective:

Certain kinds of errors get caught by the compiler, others just disappear. Why didn’t that function run? Oops, forgot to await it. Error in the coroutine? Did you remember to launch with the right params, if not, it doesn’t percolate up. I still find threads easier to wrap my head around.

Michael Kennedy offered some additional insight:

The [GIL] is so omnipresent that most Python people never developed multithreaded/async thinking. Because async/await only works for I/O bound work, not CPU as well, it’s of much less use. E.g. You can use in on the web, but most servers fork out to 4-8 web workers anyway

So what’s going on here and can we apply the lessons to Free-Threading and Multiple Interpreters in 3.14 so that in another ten years we’re looking back and wondering why they aren’t more popular?

Problem 1: What is an asynchronous-shaped problem?¶

Coroutines are most valuable with IO-related tasks. In Python, you can start hundreds of coroutines to make network requests, then wait for them all to finish without running them one at a time. The concepts behind coroutines are quite straightforward. You have a loop (the event loop) and you pass it coroutines to evaluate.

Let’s go back to the classic use-case, HTTP requests:

def get_thing_sync():

return http_client.get('/thing/which_takes?ages=1')

The equivalent async function is clean and readable:

async def get_thing_async():

return await http_client.get('/thing/which_takes?ages=1')

If you call function get_thing_sync() versus await get_thing_async(), they take the same amount of time. Calling it “✨ asynchronously ✨” does not somehow make it faster. The gains are when you have more than one coroutine running at once.

When fetching multiple HTTP resources you can start all the requests at once via the OS network stack, then handle each response as it arrives. The important point is that the actual work — sending packets and waiting for remote servers — happens outside your Python process while your code waits. Async is most effective here: you start operations, receive awaitable handles (tasks/futures), and the event loop efficiently notifies the coroutine when each operation completes without wasting CPU on busy‑polling.

This scenario works well because:

- The remote end is handling the work in another process

- The local end (asyncio HTTP library) can yield control while waiting for the response

- Operating-Systems have stacks and APIs for managing sockets and network

That’s all fine, but I started with the statement Coroutines are most valuable with IO-related tasks. I then picked the one task that asyncio can handle really well, HTTP requests.

What about disk IO? I have far more applications in Python which read and write from files on disks or memory than I do making HTTP requests. I also have Python programs which run other programs using subprocess.

Can I make all of those async?

No, not really. From the asyncio Wiki:

asyncio does not support asynchronous operations on the filesystem. Even if files are opened with O_NONBLOCK, read and write will block.

The solution is to use a third-party package, aiofiles, which gives you async file I/O capabilities:

async with aiofiles.open('filename', mode='r') as f:

contents = await f.read()

So, mission accomplished? No because aiofiles uses a thread pool to offload the blocking file I/O operations.

Side-Quest: Why isn’t file IO async?¶

Windows has an async file IO API called IoRing. Linux has this availability in newer Kernels via io_uring. All I could find for a Python implementation of io_uring is this synchronous API written in Cython.

There were io_uring APIs for other platforms, Rust has implementations with tokio, C++ has Asio and Node.JS has libuv.

So, the asyncio Wiki is a little out of date, but

- Most production Python applications run on Linux, where the implementation is

io_uring io_uringhas been plagued by security issues so bad that RedHat, Google and others have restricted or removed its availability. After paying out $1 million in bug bounties related toio_uring, Google disabled it on some products. The issue was severe; many of the related bug‑bounty reports involved io_uring exploits.

So we should hold our horses a little while longer. Operating Systems have long held a file IO API that handles threads for concurrent IO. It does the job just fine for now.

So in summary, Coroutines are most valuable with IO-related tasks is only really true for network I/O and network sockets in Python were never blocking operations in the first place. Socket open in Python is one of the few operations which releases the GIL and works concurrently in a thread pool as a non-blocking operation.

Recap: What are the async operations in asyncio?¶

| Operation | Asyncio API | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Sleep | asyncio.sleep() |

Asynchronously sleep for a given duration. |

| TCP/UDP Streams | asyncio.open_connection() |

Open a TCP/UDP connection. |

| HTTP | aiohttp.ClientSession() |

Asynchronous HTTP client. |

| Run Subprocesses | asyncio.subprocess |

Asynchronously run subprocesses. |

| Queues | asyncio.Queue |

Asynchronous queue implementation. |

Problem 2: No matter how fast you run, you can’t escape the GIL¶

Will McGugan, the creator of Rich, Textualize, and several other extremely popular Python libraries offered his perspective on async:

I really enjoy async programming, but it isn’t intuitive for most devs that don’t have a background writing network code. A reoccurring problem I see with Textual is folk testing concurrency by dropping in a

time.sleep(10)call to simulate the work they are planning. Of course, that blocks the entire loop. But that’s a class of issue which is difficult to explain to devs who haven’t used async much. i.e. what does it mean for code to “block”, and when is it necessary to defer to threads. Without that grounding in the fundamentals, your async code is going to misbehave, but its not going to break per se. So devs don’t get the rapid iteration and feedback that we expect from Python.

Now that we’ve covered the limited use cases for async, another challenge keeps coming up. The Python GIL.

I’ve been working on this C#/Python bridge project called CSnakes, one of the features that caused the most head-scratching was async.

C#, the language from which the async/await syntax was borrowed, has far broader async support in its core I/O libraries because it implements a Task‑based Asynchronous Pattern (TAP), where tasks are dispatched onto a managed thread pool. Disk, network, and memory I/O operations commonly provide both async and sync methods.

In fact, the C# implementation goes all the way up from the disk to the higher-level APIs, such as serialization libraries. JSON deserialization is async, so is XML.

The C# Async model and the Python Async models have some important differences:

- C# creates a task pool and tasks are scheduled on this pool. The number of threads is managed automatically by the runtime.

- Python event loops belong to the thread that created them. C# tasks can be scheduled on any thread.

- Python async functions are coroutines that are scheduled on the event loop. C# async functions are tasks that are scheduled on the task pool.

The benefit of C#’s model is that a Task is a higher-level abstraction over a thread or coroutine. This means that you don’t have to worry about the underlying thread management, you can schedule several tasks to be awaited concurrently or you can run them in parallel with Task Parallel Library (TPL).

In Python “An event loop runs in a thread (typically the main thread) and executes all callbacks and Tasks in its thread. While a Task is running in the event loop, no other Tasks can run in the same thread. When a Task executes an await expression, the running Task gets suspended, and the event loop executes the next Task.” 1

Going back to Will’s comment “Of course, that blocks the entire loop”, he’s talking about operations inside async functions which are blocking and therefore block the entire event loop. Since we covered in Problem 1, that’s practically everything except network calls and sleeping.

With Python’s GIL, it doesn’t matter if you’re running 1 thread or 10, the GIL will lock everything so that only 1 is operating at a time.

There are some operations don’t block the GIL (e.g. File IO) and in those cases you can run them in threads. For example, if you used httpx‘s streaming feature to stream a large network download onto disk:

import httpx

import tempfile

def download_file(url: str):

with tempfile.NamedTemporaryFile(delete=False) as tmp_file:

with httpx.stream("GET", url) as response:

for chunk in response.iter_bytes():

tmp_file.write(chunk)

return tmp_file.name

Neither the httpx stream iterator nor tmp_file.write is GIL-blocking, so they benefit from running in separate threads.

We can merge this behavior with an asyncio API, by using the Event Loop run_in_executor() function and passing it a thread pool:

import asyncio

import concurrent.futures

async def main():

loop = asyncio.get_running_loop()

URLS = [

"https://example.place/big-file-1",

"https://example.place/big-file-2",

"https://example.place/big-file-3",

# etc.

]

tasks = set()

with concurrent.futures.ThreadPoolExecutor(max_workers=10) as pool:

for url in URLS:

tasks.add(loop.run_in_executor(pool, download_file, url))

files = await asyncio.gather(*tasks)

print(files)

It’s not immediately clear to me what the benefit of this is over running a thread-pool and calling pool.submit. We retain an async API, so if that is important this is an interesting workaround.

I find that memorizing, documenting, and explaining what is and isn’t “blocking” in Python to be confusing and continually changing.

Does the free-threaded mode make asyncio more useful or redundant?¶

Python 3.13 introduced a very-unstable “free-threaded” build of Python where the GIL is removed and replaced with smaller, more granular locks. See my PyCon US 2024 Talk for a summary of parallelism. The 3.13 build wasn’t stable enough for any production use. 3.14 is looking far improved and I think we can start to introduce free-threading in 2026 in some narrow, well-tested scenarios.

One major benefit to coroutines versus threads is that they have a far smaller memory footprint, a lower context-switching overhead, and faster startup times. async APIs are also easier to reason about and compose.

Because parallelism in Python using threads has always been so limited, the APIs in the standard library are quite rudimentary. I think there is an opportunity to have a task-parallelism API in the standard library once free-threading is stabilized.

Last week I was implementing a registry function that did two discrete tasks. One calls a very slow sync-only API and the other calls several async APIs.

I want the behavior that:

- Both are started at the same time

- If one fails, it cancels the other and raises an exception with the exception details of the failed function

- The result is only combined when both are complete

flowchart LR Start([Start]) --> Invoke["tpl.invoke()"] Invoke --> f1["f1()"] Invoke --> f2["f2()"] f1 -->|f1 -> T1| Join["Tuple[T1, T2]"] f2 -->|f2 -> T2| Join Join --> End([End])

Since there are only two tasks, I don’t want to have to define a thread-pool or a set number of workers. I also don’t want to have to map or gather the callees. I want to retain my typing information so that the resulting variables are strongly typed from the return types of function_a and function_a. Essentially an API like this:

import tpl

def function_a() -> T1:

...

def function_b() -> T2:

...

result_a: T1, result_b: T2 = tpl.invoke(function_a, function_b)

This is all possible today but there are many constraints with the GIL. Free-threading will make parallel programming more popular in Python and we’ll have to revisit some of the APIs.

Problem 3: Maintaining two APIs is hard¶

As a package maintainer, supporting both synchronous and asynchronous APIs is a big challenge. You also have to be selective with where you support async. Much of the stdlib doesn’t support async natively (e.g. logging backends).

Python’s Magic (__dunder__) methods cannot be async. __init__ cannot be async for example, so none of your code can use network requests in the initializer.

Async properties¶

This is an odd-pattern but I’ll keep it simple to illustrate my point. You have a class User with a property records. This property gives a list of records for that user. A synchronous API is straightforward:

class User:

@property

def records(self) -> list[RecordT]:

# fetch records from database lazily

...

We can even use a lazily-initialized instance variable to cache this data.

Porting this API to async is a challenge because whilst @property methods can be async, standard attributes are not. Having to await some instance attributes and not others leaves a very odd API:

class AsyncDatabase:

@staticmethod

async def fetch_many(id: str, of: Type[RecordT]) -> list[RecordT]:

...

class User:

@property

async def records(self) -> list[RecordT]:

# fetch records from database lazily

return await AsyncDatabase.fetch_many(self.id, RecordT)

Anytime you access that property, it needs to be awaited:

user = User(...)

# single access

await user.records

# if

if await user.records:

...

# comprehension?

[record async for record in user.records]

The further we go into this implementation, the more we wait for the user to accidentally forget to await the property and it fails silently.

Duplicated implementations¶

The Azure Python SDK, a ginormous Python project supports both sync and async. Maintaining both is achieved via a lot of code-generation infrastructure. This is ok for a project with tens of full-time engineers, but for anything small or voluntary you need to copy + paste a lot of your code base to create an async version. Then you need to patch and backport fixes and changes between the two. The differences (mostly await calls) are big enough to confuse Git. I was reviewing some langchain implementations last year which had both sync and async implementation. Every method was copied+pasted, with little behavioral differences and their own bugs. People would submit bug fix PR’s to one implementation and not the other so instead of merging directly, maintainers had to port the fix, skip it, or ask the contributors to do both.

Backend fragmentation¶

Since we’re largely talking about HTTP/Network IO, you also need to pick a backend for sync and async. For synchronous HTTP calls, requests, httpx are suitable backends. For async, its aiohttp and httpx. Since neither are part of the Python standard library, the adoption and support for CPython’s main platforms is out of sync. E.g. as of today, aiohttp has no Python 3.14 wheels, nor free-threaded support. UV Loop, the alternative implementation of the event loop has no Python 3.14 support, nor any Windows support. (Python 3.14 isn’t out yet, so it’s reasonable to not have support in either open-source project).

Testing overhead¶

Further down the copy+paste maintainer overhead is the testing of these APIs. Testing your async code requires different mocks, different calls and in the case of Pytest a whole set of extensions and patterns for fixtures. This situation is so confusing I wrote a post about it and it’s one of the most popular on my blog.

Summary¶

In summary, I think the use cases for asyncio are limited (mostly for reasons beyond the control of asyncio) and this has constrained it’s popularity. Maintaining duplicate code-bases is a burden.

FastAPI, the web framework that’s async from-the-ground-up grew in popularity again from 29% to 38% share of the web frameworks for Python, taking the #1 spot. It has over 100-million downloads a month. Considering the big use-case for async is HTTP and network IO, having the #1 web framework be an async one is a sign of asyncio’s success.

I think in 3.14 the sub-interpreter executor and free-threading features make more parallel and concurrency use cases practical and useful. For those, we don’t need async APIs and it alleviates much of the issues I highlighted in this post.