Large Language Models (LLMs) have been trained to predict the next part of a word, or “token”, based on a training model of huge volumes of written text mostly from public Internet sources. Because English is the most widely spoken language on the Internet, most LLMs are optimized to perform well in challenges with English.

LLMs have advanced capabilities for handling and generating text in many written languages. Azure AI Studio has a model catalog for exploring and comparing many models as well as giving you the ability to deploy them directly onto Azure.

In this article we explore some best practices for handling text in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean (CJK) with LLMs. This guidance applies to the following scenarios:

- Working with text mode LLMs with written CJK text

- Processing of text for vector-based, or semantic search

- Splitting or chunking text for storage in a vector database

- Reading text from documents for processing by LLMs

Tokenization¶

Before text can be processed by an LLM it needs to be converted from a text string into an array of numbers called tokens. The mapping between the word, or subword and the token is calculated using an algorithm called a Byte-Pair-Encoder (BPE). The BPE algorithm works with an encoding and iterates through a piece of text to find way of representing that text with the fewest number of tokens. There are alternative subword tokenizers, like Unigram tokenizers but for this article we will focus on BPE as it is the only choice for OpenAI GPT 3.5 and GPT 4 related models.

The number of tokens is relevant for two reasons:

- LLM APIs are billable by the number of tokens, not by the number of letters or words. All API limits and throttling is configured to tokens.

- The recall performance of LLMs is impacted by the number of input tokens, to a sweet-spot depending on the model. Ideally, LLMs should be given a smaller “context window” from which to derive facts and information.

For example, the OpenAI embedding model text-embedding-ada-002 takes a maximum number of 8191 tokens. OpenAI GPT4-Turbo takes a maximum of 128,000 tokens as input and gives a maximum of 4906 tokens as output.

So, for those two reasons we pay more attention to the number of tokens for a piece of text than the number of characters or words when working with LLMs.

The Byte-Pair-Encoding for GPT 3.5 and GPT 4 is the cl100k_base, which has roughly 100,000 tokens. Each token is a mapping to a word, or part of a word and a unique number. In cl100k_base, the message “This is the life” is 4 tokens, “This” (2028) ” is” (374) ” the” (279) and ” life” (2324). Unlike embeddings, tokenized strings are bidirectional, so you can convert text into tokens and back again without losing information. You can try this in Python for GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 encodings using the tiktoken package:

>>> import tiktoken

>>> enc = tiktoken.get_encoding('cl100k_base')

>>> enc.encode("This is the life")

[2028, 374, 279, 2324]

>>> enc.decode([2028, 374, 279, 2324])

'This is the life'

The cl100k_base byte-pair-coding has 100,000 possible tokens to cater for every written language including alphabet writing systems like English, French, German as well as logosyllabary writing systems like those used in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean. Words or parts of words which occur frequently (like “This”) have been assigned their own token based on a probabilistic compression technique. The goal of Byte-Pair-Encoding is to encode common text into the fewest number of tokens. Words and spelling mistakes can also be tokenized using parts of words as tokens. A misspelling like “Thiss” is 2 tokens, “Th” and “iss”. Each letter in the Latin Alphabet has its own token, so the number of tokens would never exceed the number of characters for English. A general rule of thumb is that one token corresponds to around 4 characters of text for common English text.

Because CJK languages do not use the Latin alphabet, we need to consider a different ratio of words to tokens.

A good example is the character used in both Chinese (Māo) and Japanese (Neko) for cat (猫). The 猫 character is part of the Unicode CJK Unified Ideographs. As of Unicode 15.1 this includes over 97,000 characters. Since the cl100k_base encoding only has space for ~100,000 possible tokens the CJK Unified Ideographs alone would take up most space, so most characters are 2 or 3 tokens. For example, the 猫 character encoded into cl100k_base, becomes 3 tokens:

>>> enc.encode("猫")

[163, 234, 104]

These three BPE tokens are not human-readable characters and have no relation to the component parts of the character 猫 (犭, 艹, and 田) or the comprising strokes.

Commonly used characters like 三 (3 in both Chinese and Japanese) are only one token (46091). In some cases the ideographic character represents a concept like “Memorize” with fewer tokens than the English equivalent word, but this is unusual. For example, the character for memorize is 覚 (2 tokens) whereas the word “Memorize” is 3 tokens.

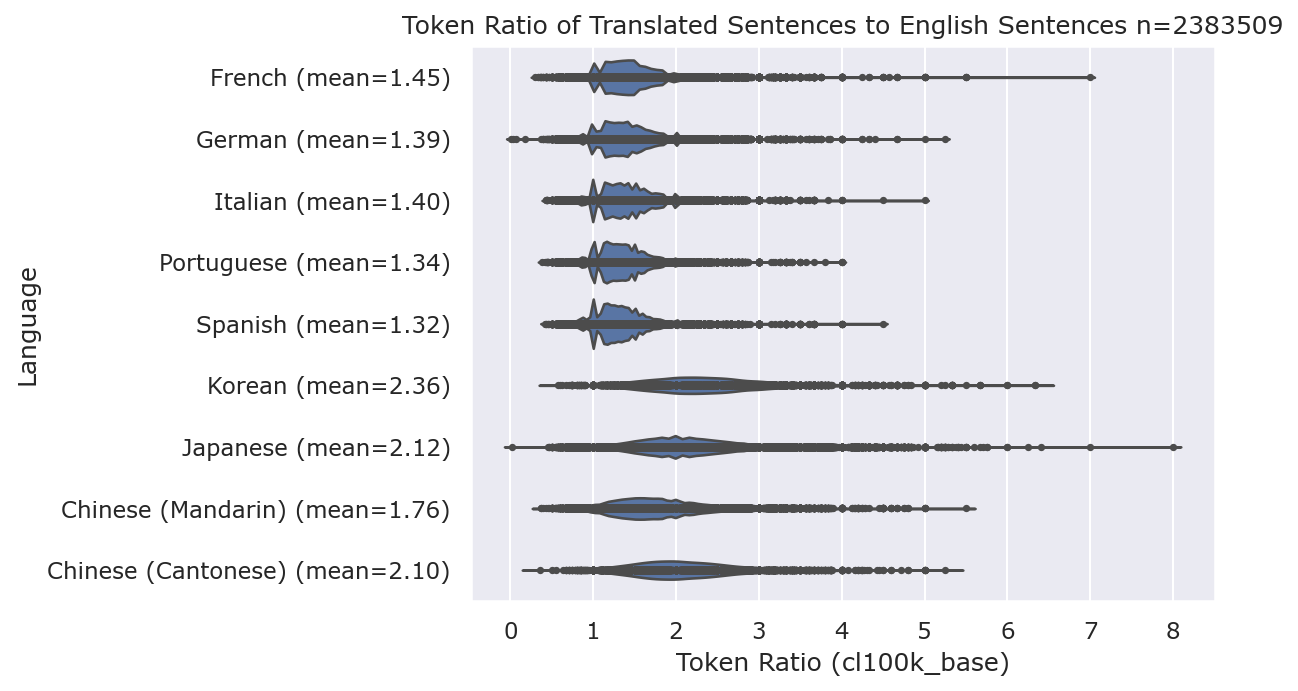

To better understand how the density of information-to-tokens, I looked a dataset of over 2 million translated sentences and measured the ratio of tokens between English and the target language. As a baseline, the most widely spoken Indo-European languages that also use the Latin Alphabet (French, German, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish) were included:

For a language like Japanese that has both Kanji and Kana, sentences can be up to 8x the number of tokens of the English equivalent, but average at 2.12x.

Mandarin has an average token ratio of 1.76x, Cantonese has 2.10x, and Korean 2.36x.

There are occasions where sentences in CJK languages will be fewer tokens than the English equivalent because the expression or phase can be said more concisely. For example, “This is the first time I’ve heard about it.” (11 tokens) can be said in Japanese “初耳だ” (5 tokens). These cases are the exception, not the rule, and it could be argued that a native English speaker would use a more colloquial term like “news to me” (3 tokens) which is why it is important to look at handwritten translations by native speakers instead of machine-translated. Ensure you are also comparing like-for-like with formal and informal text.

Korean Hangul and Tokenization¶

So far we’ve focused mostly on Japanese Kanji and Chinese. In the Korean writing system, the 14 basic consonants and 10 vowels are combined into a single syllabic symbol. In Unicode, over 11,000 precomposed syllabic symbols are defined in the Unicode Standard AC00 block. This Unicode block has over precomposed syllables so that text processors do not need to combine Hangul vowels and consonants into a single symbol. Because BPE works with Unicode code points, not with the Hangul letters the frequency of that syllable is more important to the component letters. For example, the first syllable in my name in Korean, “An” (앤) is two tokens for 앤 and seven tokens for its component letters, “ㅇㅐㄴ”:

>>> enc.encode("앤")

[31495, 97]

>>> enc.encode("ㅇㅐㄴ")

[70787, 229, 70787, 238, 159, 226, 112]

In summary, although Hangul is an elegant writing system, the complexity of the Unicode implementation impacts the token density. You would think that with 40 basic letters, Korean would have a better token density to Japanese which has 2 writing systems and thousands of characters, but instead the opposite is true. Expect a ratio of 2.36x the number of tokens for Korean than the equivalent information in English.

Text Splitting¶

When dealing with text inputs to an LLM, whether for an embedding model or for a completions model you have a limit on the number of input tokens. A common use case for embeddings models is to convert blocks of text into embeddings (or vectors) and then use a similarity algorithm to find similar text. This is particularly useful for semantic search. Azure AI Search offers this feature with both Vector Search and Semantic Search. For both technologies there is a limit to the number of input tokens that can be vectorized in the input model. There is also a “sweet spot” for the number of documents or tokens to use with completion models for the relevance of the similarity results. Even though embedding models support thousands of input tokens, research shows that recall performance drops off when you add more text. Think of it as presenting a 48-slide PowerPoint presentation and asking the audience to remember the 5 most important things, versus a short and snappy 5 slides with clear points.

Because written text doesn’t come nicely packaged in 512 token chunks, you have to break the text up before you create embeddings to vectorize data.

Text Splitting Strategies¶

When you are working with an LLM with a maximum input size smaller than the amount of data you have, you need to split up the text into chunks. For example, in a search-based RAG application large documents in a search index are broken into smaller pieces so that they can be scanned and searched quickly.

Text splitters work by looking for meaningful chunks, such as pages, paragraphs, or sentences. A 100-page document could be split into all the paragraphs, and if some of those paragraphs were larger than the maximum chunk size, they could be split again using sentences as the separator.

There are two commonly used types of splitters for use with LLMs. Character splitters, which split on the number of characters and look for a logical end to a sentence, like a full-stop. Then there are token splitters, which encode the text and break it into chunks based on the number of tokens. Both approaches have challenges with CJK text which we will explore with examples.

Character Splitters¶

Character splitters work on a target number of characters per chunk and a separator or list of separators to use for splitting. For example, Langchain’s CharacterTextSplitter splits on a single separator, defaulting to a double line-break (commonly found in paragraph separators):

from langchain_text_splitters import CharacterTextSplitter

text_splitter = CharacterTextSplitter(

separator="\n\n",

chunk_size=300,

chunk_overlap=0,

length_function=len,

)

Despite the chunk size being set to 100 characters in this example, if the paragraphs are beyond 100 characters this splitter will yield results beyond 100. Instead, recursive character splitters like RecursiveCharacterSplitter work by inspecting the length of the chunks and if the chunk is too large, splitting again. This technique is useful when combined with the approximation that 3 characters are roughly 1 token for English text. So you could efficiently split text into 100 token chunks by setting a maximum chunk size of 300 characters:

text_splitter = RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter(

chunk_size=300,

chunk_overlap=0,

length_function=len,

)

Recursive text splitters like Langchain’s take a list of separators, instead of one. By default, most recursive text splitters will use full stop, question marks, exclamation points and spaces.

There are two challenges when using recursive text splitters with CJK text. The first major challenge is the ratio of tokens to text varies greatly between languages in the BPE. It is very difficult to set a target chunk size in characters when the LLM inputs are measured in number of tokens.

The second challenge is that Chinese and Japanese written languages have different written separators for text. Korean uses spaces between words and the standard full stop (.) character for the end of sentences. Neither Japanese or Chinese (simplified or traditional) use spaces between words and the Unicode characters for the end of sentences differs to those in Latin Alphabet based languages. For example, the character 。 is more commonly used in Japanese than . to mark the end of a sentence.

These differences are documented in the W3C Requirements for Japanese Text Layout, a more up-to-date version of the JIS X 4051 standard for specifying layouts with Japanese text. In this document there are a list of characters for brackets and parenthesis as well as sentence endings. When using recursive character splitters, I recommend overriding the list of separators to include these symbols. The following example is illustrative and not an exhaustive list:

SEPARATORS = [

"\n\n", ".", # Paragraph boundary and ASCII full stop

"。", ".", # Logographic and full width full stop

"!", "!", # ASCII and full width exclamation mark

"?", "?", # ASCII and full width question mark

",", "、", ",", # ASCII, logographic, and full width comma

]

text_splitter = RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter(

separators=SEPARATORS,

chunk_size=300,

chunk_overlap=0,

length_function=len,

)

Token Splitters¶

Another approach is to split chunks based on the number of tokens. These splitters work by encoding the text into a single token stream and then breaking the stream into chunks at the specified length with optional overlapping.

For example, Langchain’s tiktoken splitter will split exactly at the specified boundary. For example if you set a chunk size of 500 tokens, you can break a piece of text into those chunks:

from langchain_text_splitters import TokenTextSplitter

import tiktoken

with open('test_ja.txt', encoding='utf-8') as f:

input_text = f.read()

bpe = tiktoken.encoding_for_model('gpt-4')

text_splitter = TokenTextSplitter(model_name="gpt-4", chunk_size=500, chunk_overlap=0)

texts = text_splitter.split_text(input_text)

for text in texts:

print("Tokens={0}, Characters={1}, Text={2}".format(len(bpe.encode(text)), len(text), text))

print("---")

A benefit of this approach is that chunks will be at exactly the number of specified tokens. However, a major downside with this approach when used with CJK text is that chunks can be split in the middle of a character because characters can be multiple tokens. Using token based splitters directly will yield unexpected results as the beginning and end of some chunks will be illegible fragments of Unicode characters.

Hybrid Splitters¶

As shown, neither character-based recursive splitters nor token-based splitters are ideal for CJK languages. Instead, I recommend combining the two approaches into a hybrid splitter uses the token length of the chunk as the mechanism for further splitting instead of the character length. For Langchain, you can override the RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter to use the token encoding to measure the length and split until an optimal chunk size is found:

from langchain_text_splitters import RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter

text_splitter = RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter.from_tiktoken_encoder(

model_name="gpt-4",

chunk_size=500,

chunk_overlap=0,

separators=SEPARATORS

)

This method benefits over character encoding because the chunk size is closer to the target token count, and it is beneficial to token-based splitters because it can’t yield invalid strings.

A quirk to note of Langchain’s splitter is that the separator will appear at the beginning of the chunk, not the end. You can remove the punctuation using the keep_separator=False argument.

At Microsoft, we have also developed a custom recursive splitter for our RAG applications designed for CJK text that uses token-length as the function to further split. This splitter implements the full list of separators in the W3C Requirements for Japanese Text Layout. Text split using this method will break at a meaningful boundary like a sentence ending, if possible and always yield chunks within the token length specified, no matter the language. This splitter is part of the prepdocs tool for our Semantic Search RAG Sample Application on GitHub and includes PDF parsing and GPT-Vision support with PDF images.

Overlapping Guidelines¶

When using chunking for search indexes in a vector store, you want to keep related information in the same chunks wherever possible. With large chunk sizes, the page, paragraph, or chapter of a document is a reliable marker of meaning but with smaller chunk sizes you may find yourself needing to split paragraphs between chunks. If important information is split between chunks it can be lost entirely to a similarity search algorithm. As a workaround, you can increase the overlap between chunks to an optimal size of 10-25%. This won’t catch all cases if the chunk size is particularly small, but it does improve recall rates.

Right-to-Left Text Layout¶

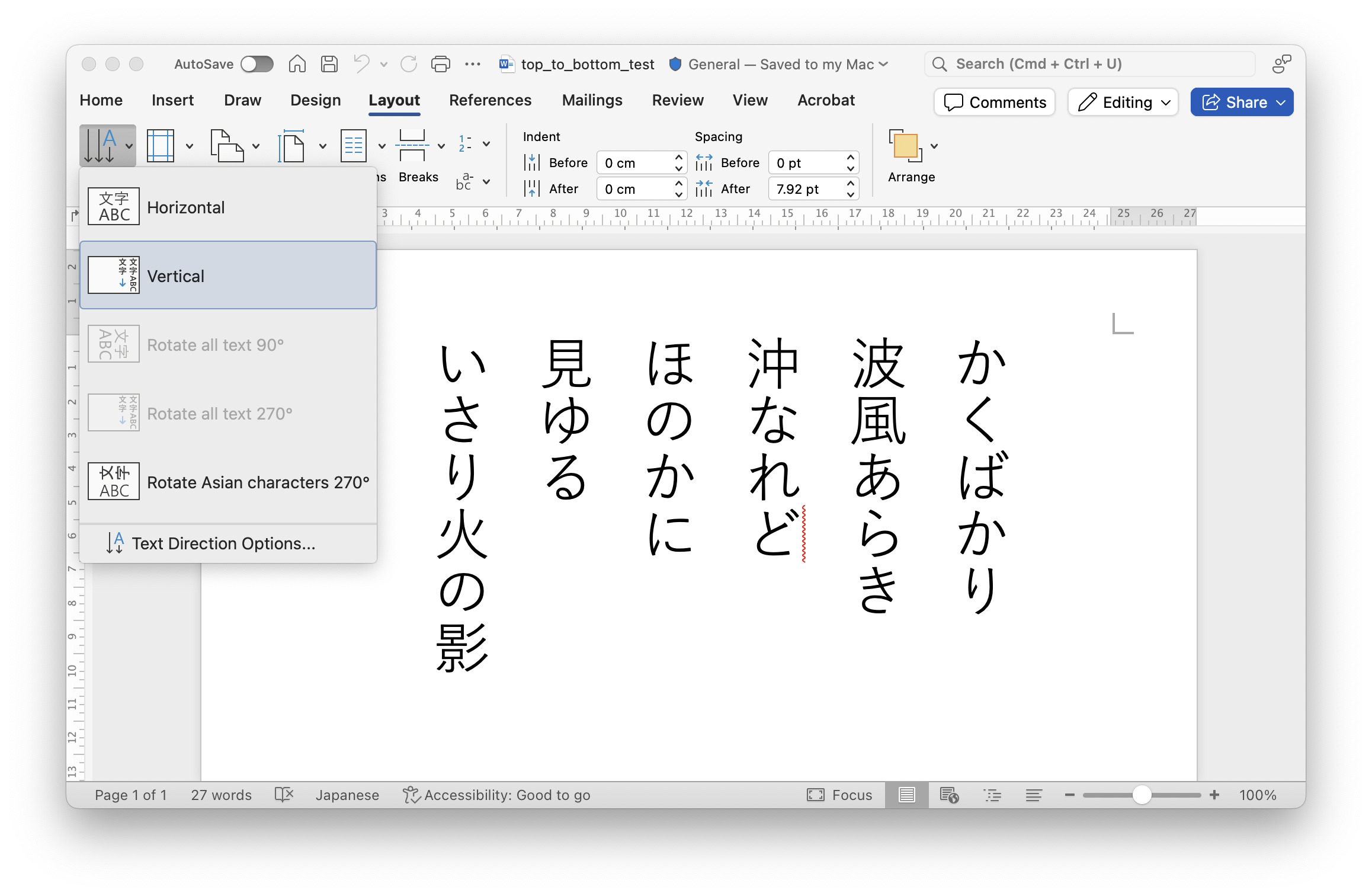

All CJK languages have a historical layout where text is written in columns and read top-to-bottom and right-to-left. Large Language Models predict the next token in a string of text based on the probability. This doesn’t change with top to bottom layout, but you do need to pay special consideration to how the text is processed from a file format.

Microsoft Word for example has a Text Layout option where text can be written in a top to bottom orientation. When using the .DOCX format, each column is stored as a paragraph and typically no punctuation is used to mark the end of a column:

When reading top to bottom orientation from Python, the results depend on what format the file was stored. If the file is retained in DOCX format you can use any OpenXML parser, like python-docx to read the file and iterate through the paragraphs.

>>> import docx

>>> doc = docx.Document('top to bottom.docx')

>>> for para in doc.paragraphs:

... print(para.text)

...

かくばかり

波風あらき

沖なれど

ほのかに

見ゆる

いさり火の影

Unlike left-to-right paragraphs where text will be one or many sentences, top to bottom orientation will be a paragraph per sentence, so you may want to merge the paragraphs with a period before embedding.

If the document is stored as PDF, results will vary dramatically between the tool used to create the PDF and the library used to read the PDF. You will find that most PDF libraries will extract the text either in the wrong order (left to right), or in the right order but with a line break between each character:

>>> import pypdf

>>> reader = pypdf.PdfReader(open('TopToBottom_Test.pdf', 'rb'))

>>> reader.pages[0].extract_text()

' \nか\nく\nば\nか\nり 波\n風\nあ\nら\nき 沖\nな\nれ\nど ほ\nの\nか\nに 見\nゆ\nる い\nさ\nり\n火\nの\n影 \n '

If possible, retain documents in OpenXML format or a format that specifically supports top to bottom orientation before extracting text.

Summary and Recommendations¶

- When working with CJK you need to factor in roughly twice the number of tokens to text than you would with English.

- Use a hybrid token and character-based recursive text splitter

- Customize any text splitters with the W3C standard for Japanese text

- Look for right to left documents and check for invalid parsing in PDFs, if possible keep in a format like Word OpenXML docx.