For a while now I’ve been trying to use LLMs to optimize code. I’ve given many talks on performance in dynamic languages and published a thesis on this last year. Chasing code performance comes down to some key steps:

- Understanding how the code runs

- Understanding how the system runs it (memory, disk, CPU caching)

- Understanding how to profile the code and understand where it is slow

- Understanding tricks and patterns to improve it

LLMs are great at the fourth step. They have seen more code than 1000 programmers will ever see in a lifetime and they can recognize patterns in all commonly used languages. They also know the theory of how code runs. They’ve “read” all the Computer Science textbooks and know all the algorithms.

The secret sauce is knowing what to optimize and being able to apply experience and knowledge to experimenting.

Take these two recent examples that I think an LLM would never have come up with if you gave it the code and said “make this faster”:

- OpenAI’s Python SDK has a performance option when using the embeddings API to use the NumPy package to decode the floating point values. I submitted an alternative approach built into Python which is 20% faster, a handful of lines of code and for the average user is 420% faster.

- Ken Jin submitted a proposal to make CPython 10% faster by switching the interpreter to tail-calling

When I ask LLMs to optimize code they tend-to give some generic text-book guidance on optimization. I just tried GPT-4o with the instruction “make this code faster” for a Python function, it said:

To make this code faster, we can consider the following optimizations:

Avoid repeated attribute lookups: Store frequently accessed attributes in local variables.

Optimize the loop: If possible, optimize the loop to reduce overhead.

If possible, optimize the loop to reduce overhead. - well thank you for that insight.

The key to being successful with LLMs is to provide context and clear instructions. But, there is so much implicit knowledge in how to make a function or block of code faster. This information either doesn’t fit in the context window of ~4000 tokens, or the instructions are so complicated the LLM can’t handle them all and skips over important ones to produce something slower or incorrect.

This is where reasoning models come in.

As an experiment I wanted to see how the DeepSeek-R1 reasoning model could handle a complex optimization problem.

To make the experiment even more interesting, I picked a block of code deep inside Python itself that handles the arithmetic of large multiplications and large exponent calculations (e.g. 2**34443).

If the AI makes it faster and doesn’t break Python, it would make math faster in Python. A tempting prize.

I saw a similar post from the Ollama.cpp project where DeepSeek-R1 was used to apply optimizations to a codebase. The developer shared their prompt and it gave a clear example of the output. Their prompt was different to what I’m trying here because it gave a very clear templated example.

How is a reasoning model different to other LLMs?¶

Reasoning models are types of LLMs specialized for complex tasks. Reasoning models typically perform significantly better on Math tests or with brain teasers than traditional LLMs. Reasoning models can be given long lists of constraints and will explore different paths recursively to solve a problem.

DeepSeek-R1 is not the only reasoning model. OpenAI’s o1, o1-mini, and o3 models are reasoning models. Qwen QVQ is a reasoning model from Alibaba that I was playing with in December to try and solve a game of Set.

The problem statement¶

For DeepSeek-R1 I wanted it to optimize some C code inside Python itself. This code is old and written by some very smart people, many of whom have created the knowledge the LLMs are trying to imitate.

I wanted the LLM to reason why the following code wasn’t optimized by the compiler and whether the code itself could be changed, without changing. The new code must be equivalent, and it must meet a long list of constraints.

This is a hard problem that goes well beyond “optimize the loop to reduce overhead.”

Here is the code:

static digit

v_iadd(digit *x, Py_ssize_t m, digit *y, Py_ssize_t n)

{

Py_ssize_t i;

digit carry = 0;

assert(m >= n);

for (i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

carry += x[i] + y[i];

x[i] = carry & PyLong_MASK;

carry >>= PyLong_SHIFT;

assert((carry & 1) == carry);

}

for (; carry && i < m; ++i) {

carry += x[i];

x[i] = carry & PyLong_MASK;

carry >>= PyLong_SHIFT;

assert((carry & 1) == carry);

}

return carry;

}

This function adds two vectors of digit where the length of vector x is m and the length of vector y is n. This function does inplace addition (so the result is written to the vector x) and it returns any carried digit if it exceeds the existing length of x. To make things more complicated, Python doesn’t use base-10 to store numbers, so digit is not a value 0-9 as you might expect. This creates a harder problem for LLMs who may have seen hundreds of similar bits of inplace vector add functions with base-10.

The optimization path I’m seeking is for the LLVM Clang compiler to vectorize the instructions inside the loop to more efficient vector arithmetic. The problem with vectorization optimizations is that they require a lot of conditions to be met before they can work effectively.

I wrote up all of those conditions into a prompt as the set of instructions for the LLM along with it’s task:

Your job is to suggest optimizations to C code by finding loops which could be vectorized.

The clang compiler has decided that this loop cannot be vectorized, because it fails to meet one of the following rules. Your job is to work out which of these rules is not met in the code, then suggest an alternative block of code that would meet these requirements. The vectorizer will compile SIMD instructions into the program. This is efficient when the instructions in the code are the same for each iteration and they can be executed in parallel by multiple cores. If the loop contains complex branching logic, then it cannot be vectorized. If you decide that a loop cannot be vectorized without simple changes, explain why.

Here are the rules and constraints for the LLVM vectorizer algorithm:

# Loop Vectorizer Rules

- The loop trip count (number of cycles) at entry to the loop at runtime.

- The number of loop cycles can not change once entering the loop. e.g. if there is a conditional continue statement, it cannot be vectorized.

- The loop must have a single entry and exit point. e.g. If there are break statements in the code, it has multiple exit points.

- The Loop Vectorizer operates on loops and widens instructions to operate on multiple consecutive iterations.

- The Loop Vectorizer supports loops with unknown trip count at compile time. The trip count does not need to be constant.

- The Loop Vectorizer can vectorize loops with runtime checks of pointers.

- The Loop Vectorizer can vectorize reductions (e.g., sum, product, XOR, AND, OR).

- The Loop Vectorizer can vectorize inductions (e.g., saving the value of the induction variable into an array).

- The Loop Vectorizer can vectorize if-conversions (e.g., flattening IF statements).

- The Loop Vectorizer can vectorize pointer induction variables (e.g., using C++ iterators).

- The Loop Vectorizer can vectorize reverse iterators (e.g., counting backwards).

- The Loop Vectorizer can vectorize scatter/gather operations.

- The Loop Vectorizer can vectorize mixed types (e.g., combining integers and floats).

- The Loop Vectorizer can vectorize global structures alias analysis (e.g., accessing global structures).

- The Loop Vectorizer can vectorize certain function calls (e.g., intrinsic math functions).

# SLP Vectorizer Rules

- The SLP Vectorizer combines similar independent instructions into vector instructions.

- The SLP Vectorizer processes code bottom-up, across basic blocks, in search of scalars to combine.

- The SLP Vectorizer can vectorize memory accesses, arithmetic operations, comparison operations, and PHI-nodes.

# Constraints

- Loops with complicated control flow, unvectorizable types, and unvectorizable calls cannot be vectorized.

- The Loop Vectorizer uses a cost model to decide when it is profitable to unroll loops.

- The Loop Vectorizer may not be able to vectorize math library functions that access external state (e.g., "errno").

- The Loop Vectorizer may not be able to vectorize loops with undefined behavior.

This is the C code to evaluate:

{{ code }}

Whatever code it produced, I would copy + paste it into CPython, see if it compiles and then run the CPython test suite to see if it worked.

Phase 0 : Trying a 70B reasoning model¶

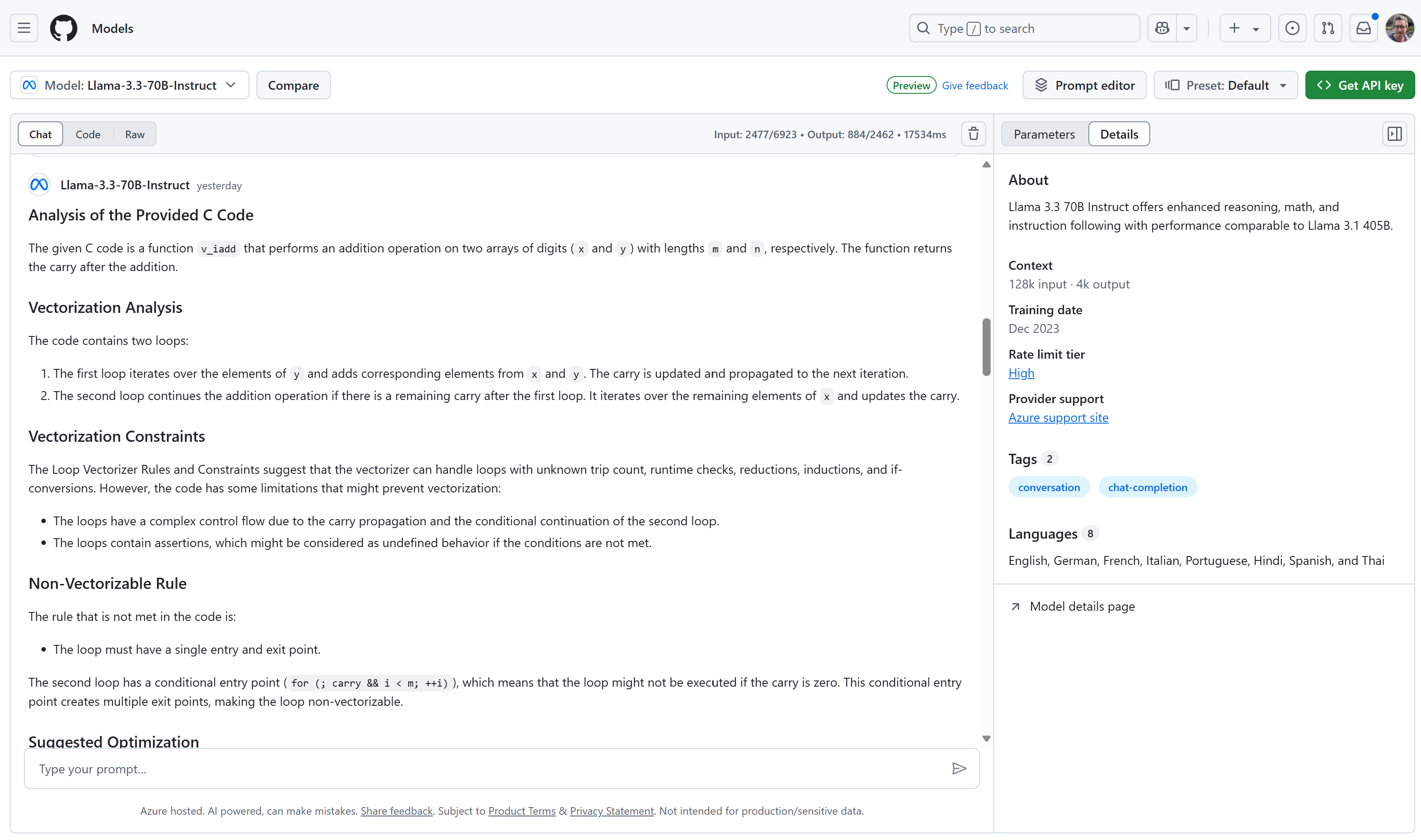

The first model I tried was Meta’s Llama 3.3 70B. “Instruct offers enhanced reasoning, math, and instruction following with performance comparable to Llama 3.1 405B.”

You can run Llama 3.3 70B directly in GitHub Models with a GitHub Account for free (which is what I did):

Analysis of the Provided C Code The given C code is a function v_iadd that performs an addition operation on two arrays of digits (x and y) with lengths m and n, respectively. The function returns the carry after the addition.

Vectorization Analysis The code contains two loops:

The first loop iterates over the elements of y and adds corresponding elements from x and y. The carry is updated and propagated to the next iteration. The second loop continues the addition operation if there is a remaining carry after the first loop. It iterates over the remaining elements of x and updates the carry. Vectorization Constraints The Loop Vectorizer Rules and Constraints suggest that the vectorizer can handle loops with unknown trip count, runtime checks, reductions, inductions, and if-conversions. However, the code has some limitations that might prevent vectorization:

The loops have a complex control flow due to the carry propagation and the conditional continuation of the second loop. The loops contain assertions, which might be considered as undefined behavior if the conditions are not met. Non-Vectorizable Rule The rule that is not met in the code is:

The loop must have a single entry and exit point. The second loop has a conditional entry point (for (; carry && i < m; ++i)), which means that the loop might not be executed if the carry is zero. This conditional entry point creates multiple exit points, making the loop non-vectorizable.

Suggested Optimization To optimize the code for vectorization, we can consider the following alternatives:

Unroll the loops: If the lengths of the arrays are known at compile time, we can unroll the loops to reduce the number of iterations and simplify the control flow. Use SIMD-friendly data structures: If possible, we can use SIMD-friendly data structures, such as arrays of structs or structs of arrays, to improve the memory access patterns and reduce the number of loads and stores. Use intrinsic functions: We can use intrinsic functions, such as those provided by the compiler or libraries like SIMDPP, to perform the addition operation in a vectorized manner. Here's an example of how the code could be modified to use SIMD-friendly data structures and intrinsic functions:

Llama 3.3 Instruct then produced the following code:

#include <immintrin.h>

static digit

v_iadd(digit *x, Py_ssize_t m, digit *y, Py_ssize_t n)

{

Py_ssize_t i;

digit carry = 0;

assert(m >= n);

for (i = 0; i < n; i += 4) {

__m128i x_vec = _mm_loadu_si128((__m128i *)(x + i));

__m128i y_vec = _mm_loadu_si128((__m128i *)(y + i));

__m128i sum_vec = _mm_add_epi32(x_vec, y_vec);

__m128i carry_vec = _mm_srli_epi32(sum_vec, PyLong_SHIFT);

carry += _mm_extract_epi32(carry_vec, 0);

_mm_storeu_si128((__m128i *)(x + i), sum_vec);

}

for (; carry && i < m; ++i) {

carry += x[i];

x[i] = carry & PyLong_MASK;

carry >>= PyLong_SHIFT;

}

return carry;

}

If you squint this code looks really smart and efficient. It’s replaced first loop with another that works in steps of 4 and uses a 128-bit instruction library.

There are 2 major issues with it’s answer. Firstly, it missed the 128-bit equivalent to carry & PyLong_MASK so the answer will almost always be wrong. I told Instruct about the first issue (I’ll come to the second in a moment).

Instruct gives me the corrected code and explains it’s changes:

"In this corrected code, I've added a line to mask the sum_vec with PyLong_MASK before storing it back into the x array. This ensures that the result of the addition is properly masked to fit within the digit type."

The corrected code is now numerically correct. But it took a human to intervene and explain it was wrong to get there. The second issue is what whilst it is efficient to do the arithmetic of 32-bit integers in blocks of 4 using specialised 128-bit instructions, n is not nessecarily a factor of 4.

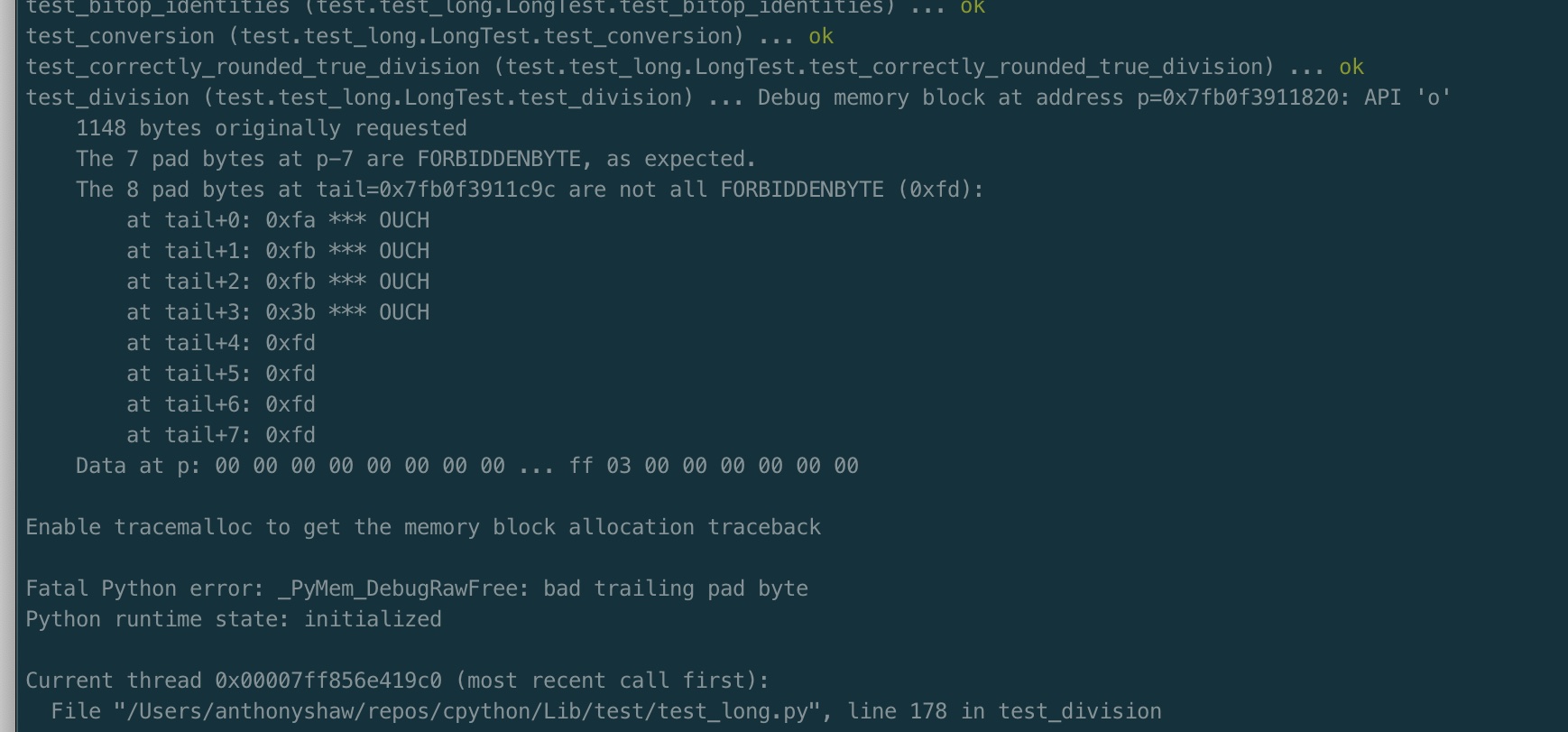

So what happens when it isn’t a factor of 4? I said I would just compile it and find out, so:

The extra numbers from the 128-bit numbers are written into someone else’s memory space, causing Python to crash every time it multiplies big numbers together. Or worse, have undefined behaviour.

I prompted it “What about overflow errors?”, it reasoned (incorrectly) why that might be happening, produced some more code that crashed and then I pushed it further “this is still overflowing” and it produced even more complicated (and wrong) code.

So the first test wasn’t successful, but it could be onto something if it were specialized where n is a multiple of 4.

Phase 1 : Trying the little model that could¶

Next I wanted to try a distilled DeepSeek-R1 model. These are available on Ollama so that you can download them and run them on normal hardware. I have a 4-year old laptop running Windows and an onboard Nvidia GPU. I can run both the 7B and 8B models on this hardware.

To test I used the [AI Toolkit for VS Code] interface to ollama (screenshot.)

Phase 2 : Trying a larger model¶

-

Explain what happens with the 14B model

-

Show the new code

- Show the benchmark

Phase 3 : Running the full 371B parameter model¶

Talk about the Azure model

Show the result.